You must login/create an account to view this content

Menu

General – Students and Graduates

You must login/create an account to view this content

Planning for a future expansion into Asian markets? Export expert, Siddharth Shankar, has six pieces of advice to offer

There are big profits to be made for companies looking to expand their products into Asia, but what’s the best way to break into the Asian marketplace? Here are six top tips:

1. Follow demand

Where is there already a market for your product? Heavy industrial products are valued in countries, such as India, China, Thailand and Cambodia, where huge infrastructure construction is needed but where there is a shortfall in the country’s own heavy industry manufacturing. Energy products, relating to both fossil fuels and renewable energy, are very competitive in ASEAN countries. Luxury goods are popular in parts of the Middle East and Japan.

2. Understand your target market

Gaining an in-depth understanding of the local market is the key. This includes understanding local culture, legal restrictions and regulations, language barriers (finding reliable translators if necessary) and setting up a local network of individuals and organisations you’ll need to work with.

3. Don’t sweat the distance

Exporting to Asia is becoming more straightforward. The fast-improving infrastructure in many countries, coupled with cheap warehousing and logistical costs mean it’s more and more feasible to trade there. Lower labour costs also allow western businesses to operate in these markets with less of the risk normally associated with entering a new export market. Adoption of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and corporate governance codes by many countries across Asia is also making the exporting process easier.

4. One size doesn’t fit all

PR and marketing activity needs to be tailored to the specific region in Asia to which you’re exporting; it isn’t sufficient to target Asia as a whole. To take UK brands as an example, their products’ lineage and heritage can make them attractive to consumers in Asia, in part due to the historical legacy of British colonialism in the region.

However, the key to success is in understanding that each local market is separate and treating it as such. A Korean woman’s shopping habits are completely different to those of her Chinese counterpart, so seeking advice on this from a local partner is key.

5. Smaller brands are gaining traction too

Asian markets are now starting to recognise smaller brands too. Look, for example, at the recent success of UK brands such as Burberry, MG motors, Rolls-Royce and Dyson [the latter of which has even shifted its headquarters to Asia in the past year] in China, India and ASEAN countries.

The reasons behind this are more complex than a mere show of wealth. A big brand product, such as LV or Coach, that people purchase and show to friends and colleagues might demonstrate the owner is rich. But other purchases might convey that the owner has a certain taste. This mindset comes from the new generation of consumers representing Asia’s middle classes, and it’s key to tap into this as a smaller brand.

6. Don’t go it alone

Many markets in Asia have a tendency to favour their own national organisations over companies from overseas – so it might be an idea to partner up with a local organisation. However, it’s important to make sure you pick a knowledgeable and trustworthy company.

Avoid signing up with any partners without carrying out thorough background research and providing clear and enforceable paperwork and responsibilities. The methods of conducting business in Asia are very different, so it’s important to be as clear as possible before you sign on the dotted line.

Siddharth Shankar is a leading expert in exporting and CEO of Tails Trading, a firm helping UK SMEs to export their goods.

You must login/create an account to view this content

Expanding a business internationally can be challenging, but Asia offers five major markets and many of the world’s fastest-growing economies, writes Siddharth Shankar

Expanding a business internationally is a difficult undertaking at any time. But with the current geopolitical tensions and heightened uncertainty, you would be forgiven for thinking this isn’t the time to take a risk on an overseas launch. However, international expansion could prove key to beating gloomy forecasts.

Many of the world’s fastest-growing economies are in Asia. India, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, the Philippines, China and Mongolia were all expected to grow by between 7.4% and 6.2% over the course of 2019, for example. This makes Asia an increasingly important, and lucrative, focus for businesses based outside the region. When it comes to international expansion, there may now be more opportunity for firms within Asia than within the European Union.

Research by HSBC has found that approximately 70% of future world growth will be from emerging economies. And analysis from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development reveals that Asian economies will be larger than the rest of the word combined in 2020. It’s therefore becoming increasingly important that businesses shift their focus to markets that will, in the future, dominate the world stage.

Five major markets

To successfully expand into Asian markets, it’s critical not to fall into the trap of treating the continent as one homogenous market. The region is made up of five major markets – namely China, the Indian subcontinent, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries, countries in the Middle East’s Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)and East Asia. Lumping all these highly diverse regions and countries into one convenient bracket has been the downfall of many businesses. It’s crucial to understand the cultural, social, political, geographical and economic factors at play in each Asian market individually.

First, the products that will be successful in each market will be very different. Heavy industrial products, for instance, are in demand in India, Thailand and Cambodia. Huge infrastructure construction is needed within these countries, yet their own heavy industry manufacturing is relatively weak.

Energy products – relating to traditional fossil fuels and renewable energy equipment – are competitive in ASEAN countries as well as in China. China and India have now realised the increasing need to forge a cleaner and leaner path to development. Luxury goods are particularly in demand in GCC countries and Japan. Meanwhile, in China and India, the appetite for traditional beverages, such as whisky and gin from the UK, has reached a whole new level.

As well as the economic, geographic and societal factors that affect a product’s potential in Asian markets, it’s often more difficult to form an understanding of the cultural factors. This requires in-depth local knowledge. For instance, a company launching a range of hats in China might have unrivalled success selling a red hat but find a green version of the same hat would flop. This is because, within local culture, if a man wears a green hat it might mean his wife is cheating on him – never a good look! A local partner can prove essential in navigating these testing cultural nuances.

The strategy required to expand into each market is also diverse. Launching a product portfolio in Asia’s two largest markets – China and India – requires taking an altogether different approach in each case. Western products can be launched directly into China, with westernised branding, even as a new brand. Conversely, to maximise the chances of success when expanding into the Indian market, it is often advisable to expand into influential markets with links to India first – for instance, Singapore or the United Arab Emirates.

This allows the target segment of consumers in India to form an understanding of the brand before it is available in India, thereby piquing demand for it. Indian consumers tend to follow their culture, tradition and values strictly. As a result, overseas companies are often forced to give an ‘Indian touch’ to their products and marketing in order to succeed.

Regional differences

Even within a country, it’s important to be aware of the vast cultural differences that often exist between one region, or city, and another.

You would probably be forgiven for thinking that the capital city in each location is the best place to launch a new business. But sadly, it is not that simple. Not all capitals work. To give a European example of what I mean, it’s notoriously difficult to do business in Rome. It might be the heart of Italy’s political and religious institutions, but if you were going to launch a fashion business in Italy, you would almost certainly bypass Rome and head straight for Milan, with all its design and fashion credentials and networks.

It’s the same in each of the five major markets in Asia. The capital cities may be the perfect place to build political alliances – but that doesn’t mean they are the best place from which to launch a particular product or brand. Often, looking beyond the capital and targeting smaller cities, and even towns, can deliver better results.

You may not have heard of places like Tangshan and Sanya in China – but they are exactly the sort of cities that are worth thinking about. Both cities have local economies that are thriving due to huge local wealth, or large tourist attractions. Both also have effective infrastructure and would deliver excellent results for the launch of brands from certain industries.

Cultural identity

Deciding which city to launch from is not even necessarily about choosing one of the biggest cities. Do your research – think about the cultural identity and interests of your target customer and work out where they are most likely to be based. It’s the only way to find the city with the best fit and consumer base for your product.

Before honing in on a launch city, it is also worth spending time reflecting on the bigger picture. Each of Asia’s five major markets presents exciting growth opportunities.

India has a population almost equal to that of China but a GDP growth rate that is almost double China’s. Looking to East Asia, Japan is the world’s third-largest economy, while South Korea has one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. Meanwhile the ASEAN region, which includes Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia, has a combined population of 640 million people and an economy worth over $2.8trn USD, with increasingly open internal trade.

Market focus

So which specific markets within Asia should businesses focus on? Let’s take a more in-depth look at two very different, but highly promising opportunities:

A. The major market: India

India’s GDP growth forecast for 2019 is 7.3%, making it one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. Rising salaries mean the region has a burgeoning middle class, with an increasingly disposable income. According to the Economist, HSBC recently estimated that the size of India’s middle class in India had reached 300 million, a figure it predicts will rise to 550 million by 2025.

The demand for products and brands in India is at an all-time high and this is set to continue for the foreseeable future. Indian consumers have become more value sensitive than price sensitive. If they feel that a particular product offers them more value, they are often willing to buy the product, even if the price is high.

India is a multi-religion country which has a population of around 1.4 billion people. There are four broad segments to the market:

• The socialites: socialites belong to the country’s elite. They like to shop for luxury products, travel in high-end cars and buy opulent villas. They are always looking for something different. Socialites are also very brand conscious and would go only for the best-known brands in the market.

• The conservatives: the conservatives belong to the middle classes and are often a reflection of the true Indian culture. They are traditional in their thought processes, slow in decision making and they seek a lot of information before making any purchase.

• The female profesionals: the so-called ‘working woman’ segment of society has seen tremendous growth in recent years and, as they have become empowered in the workplace, their impact on consumer trends has boomed.

• Youth segments: the younger generation is optimistic and enthusiastic. They believe in having a modern lifestyle, are brand cautious and are often ready to pay for quality.

B. The market to watch: Thailand

Thailand is the second-largest economy in the ASEAN, accounting for 17% of ASEAN GDP. There have been huge changes in Thailand over the past 40 years, transforming it from a low-income country to an upper-income country. After a slowdown between 2015 and 2017, Thailand’s economy looks to be on the up once more, with a growth rate of 4.1% in 2018.

It is increasingly easy to do business in Thailand, as the infrastructure improves and the government makes positive regulatory reforms. There is a growing middle class and, in the capital of Bangkok, new luxury brand shopping centres are springing up.

In conclusion, the combination of fast-growing Asian economies and a troubled eurozone means there is a lot of opportunity for firms to expand into Asia. While in-depth research into the complex cultural, social and economic factors of launching a brand into each individual market within Asia is essential to avoid falling into common exporting traps, the potential rewards are high.

Siddharth Shankar is a leading expert in exporting and CEO of Tails Trading, a firm helping UK SMEs to export their goods.

You must login/create an account to view this content

Aga Khan University’s Eunice Ndirangu on working to impact healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa in the time of Covid-19 with a training programme established in partnership with the social impact arm of pharmaceutical firm and established employer of business graduates, Johnson & Johnson

If this pandemic has shown us anything, it is that we still do not have enough trained healthcare workers, particularly nurses. According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) State of the World’s Nursing report released earlier this year, nurses are the largest occupational group in the health sector, accounting for 59% of the health profession. As a result, WHO declared 2020 the Year of the Nurse and the Midwife, to acknowledge the crucial role they play in healthcare systems. As Covid-19 shook health defences worldwide, everyone retreated indoors to practice social and physical distancing, leaving doctors, nurses, midwives, paramedics and other healthcare workers on the frontline, toiling tirelessly to heal the world.

Partnering with Johnson & Johnson to deliver professional development and training

Since 2001, the Aga Khan University’s School of Nursing and Midwifery East Africa (AKU-SONAM EA) has trained nurses and graduated more than 2,600 nurses and midwives. We have had the privilege to train even more nurses and midwives through continuous professional development courses. None of this would have been accomplished without the backing of Johnson & Johnson Foundation (JJF), formerly the Johnson & Johnson Corporate Citizenship Trust. From 2001, it has provided scholarships to students who would not have been able to access quality higher education without its intervention. Nursing and midwifery leaders in many of Kenya’s largest health institutions can point to Johnson & Johnson as the organisation that sponsored their nursing education.

After the pandemic broke, AKU-SONAM EA partnered with the World Continuing Education Alliance (WCEA), the International Council of Nurses (ICN) and Johnson & Johnson once again to support frontline health workers. The partnership has resulted in a targeted training programme for nurses and midwives in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East through the establishment of a Covid-19 curriculum based on WHO training guidelines which will reach nursing networks through ICN’s partnerships.

Putting the scale of the East Africa’s healthcare challenge in perspective

Europe bore the initial brunt of the outbreak as the world was confronted with the reality of fatigued and infected healthcare workers, dying patients, collapsing economies and a generally grim picture of what was to happen to the rest of the world. On seeing this, East African governments embarked on various measures to cushion against the devastation we all witnessed.

In Kenya, contact tracing, the cessation of movement and a countrywide curfew were used to contain the spread. Tanzania deployed a more ‘open’ strategy which resembled the path chosen by Brazil, and in Uganda there was an initial total lockdown where only essential workers were allowed to move around through private transport. These different strategies adopted by neighbouring countries lay a foundation for regional misunderstanding, but all three countries shared one thing in common: an evident shortage of capable healthcare workers.

WHO puts the number of nurses per 10,000 members of the population at 11.7 in Kenya, 12.4 in Uganda and 5.8 in Tanzania. To put this into context, in the US, for every 10,000 people there are 145.5 nurses. As I write this, the US has the highest number of Covid-related deaths in the world but has more than 10 times the nursing workforce of any East African country. These statistics give a slight preview of the amount of havoc a large-scale breakout of the pandemic would wreak on East Africa.

The nursing workforce is a benchmark because worldwide, nurses form the largest percentage of health personnel. In Kenya, nurses are 85.9% of the healthcare workforce and in many community settings, nurses are the only healthcare representatives available at the grassroots. This is why training them is so vital for vulnerable societies.

Addressing knowledge gaps: Covid-19 training courses

Drawing from the expertise of our faculty, the new partnership with Johnson & Johnson enabled several courses to be developed in April. The courses relate to Covid-19 infection prevention and control, psychosocial support for patients in isolation and healthcare workers. Additionally, we have courses covering Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for various settings, courses in care for the elderly during the pandemic as well as a course on the management of critical care patients infected with Covid-19. The ‘Covid-19 Infection Prevention and Control’ course is also available in Spanish and will soon be available in several other languages to ensure that no one is left out. The initiative launched in Kenya in April and will soon launch in Uganda and other countries, targeting up to 600,000 nurses and midwives in total who have registered with their national nursing councils. Some of our faculty have received interesting feedback from their international colleagues who have accessed the programme even in the US.

My inspiration for this project comes from interacting with some of the nurses in our work-study programmes. In the beginning, nurses were unsure about how to handle infected patients and nearly put their tools down. There were no standard operating procedures on how to handle patients, there was minimal PPE available for frontline workers and they were generally ill-equipped and operating in the dark. Even when PPEs was available, some nurses and midwives were unsure about which ones were necessary to avoid infection and how to take them off without contaminating themselves at the end of a long shift. One Kenyan nurse shared a story of how in the event of discharging a patient who had recovered from the virus, the patient hugged her. This nurse was scared and her whole team had to be quarantined and tested for Covid-19. Luckily, these tests turned out negative but revealed the need for protocols on how to handle similar situations. A hug in the wrong circumstances can be fatal. We forget that just like many of us, nurses still have to go back to their families and they still self-isolate while at home despite being with their loved ones.

We have seen how devastating the effects of this pandemic have been which is why I believe that it is crucial to provide nurses and midwives with access to Covid-19 resources. I hope that the courses will address important knowledge gaps for nurses and midwives across East Africa even as the disease evolves for all of us.

Dr Eunice Ndirangu (pictured above) is the Dean of the School of Nursing and Midwifery at the Aga Khan University and Chairperson of the Board of the Nursing Council of Kenya. Through nursing practice, teaching, research and policy work, she continues to influence nursing education and policy in East African healthcare systems.

You must login/create an account to view this content

You must login/create an account to view this content

Does your business risk irrelevance? It will soon if three fundamental innovation perspectives are ignored, says Berlin School of Business and Innovation’s Alexander Zeitelhack

In recent years, innovation has become a hot topic and a leading approach with regards to technology, and across many other sectors. The need for innovation and the forms it assumes are a fast-changing reality, calling for adjustments and an ability to adapt from those who are looking to make the most of this.

This article offers three different perspectives and some useful pointers to guide you through some of the still-uncharted territories of innovation.

Three key perspectives on innovation

1. There is the need for a different approach to the way we look at things in day-to-day life. When we try to solve the same problems every day, with the same methods and tools, we are ignoring the need and request for progress.

Everything around us is evolving and developing, and we need to be aware that we cannot survive with the ‘endless growth model’ of economy, as firstly, we’d run out of resources, and secondly, there will be no real improvement.

2. Looking at things we cannot account for, whether this is in business or life. These unknown elements are our enemies. Should our competitors find one of those, we could easily be replaced in the marketplace. Innovation, creation and management are the minimum protections against this threat. Combined, they can help to identify potential issues before they arise and, most importantly, allow them to be dealt with in an effective manner.

3. An invitation to broaden our horizons and outlooks. In society, there is always a need for a specific product or service, and then there is the solution, or product, that fulfils this need. This means that if we only look at what we do (inside), then we will miss what is needed on the outside. This would be a failure to reach out to both existing and potential audiences and customers, affecting our results.

Ignoring any of the three perspectives above can culminate in a loss of relevance among people and consumers. This happened to the music industry when it tried to ignore MP3 technology, and it will happen to businesses that ignore climate change.

Investing in innovation

With its ever-changing nature, it might be difficult to identify precisely how much businesses should invest in innovation. This doesn’t only apply to infrastructure, but also to a variety of elements that make for a successful business.

A business should make projections for the market size of a future market segment that it wants to explore, a bit like real estate development. Then the future profit in that segment can be calculated and, I would advise, a fivefold increase of annual profits can be planned.

A business should create a story, or narrative, for its corporate culture to attract more young entrepreneurial thinkers. This will have an effect on employer branding and internal competitiveness.

Having a clear focus on diversity – of gender, culture, language, and age – is also important. For example, younger hires that are grouped into teams with senior management might be able to convince with determination and motivation, in spite of their relative lack of experience.

It’s also a good idea to create a working space that looks and feels different, and that can become a factory of ideas. It’s worth investing in a great architect as well as hiring agile coaches and design thinking experts to lead innovation teams.

Unleash talent

For any business that is looking to make the most out of the competitive advantages of optimising operations to drive innovation and creativity, it’s imperative to begin by getting the next generation of creative, global and diverse-minded managers on board.

Make your innovation process the home and castle that these emerging talents need and don’t let the future leave you behind.

Alexander Zeitelhack is Associate Dean at Berlin School of Business and Innovation (BSBI). He has also been teaching media management, future research and social entrepreneurship at Nuremberg Institute of Technology for 25 years, where he held the position of Managing Director from 2009-2013.

An account of how a walk into the unknown and the plight of late 19th-century farmers in the southern Netherlands provided a powerful means of injecting purpose into employees of Rabobank, from the book Alive at Work

At some point, we’ve all felt underwhelmed by what we do at work – bored and creatively bankrupt. In these moments, we’ve lost our zest for our jobs and accepted working as a sort of long commute to the weekend. Yet even though we’ve all been there, it can be frustrating when our people aren’t living up to their potential. It’s exasperating when employees are disengaged and don’t seem to view their work as meaningful. It can be hard to remember that employees don’t usually succumb to these negative responses for a lack of trying. They want to feel motivated. They seek meaning from their jobs.

But their organisations are letting them down. We can do a much better job at maintaining their engagement with their work. But first, we need to understand that employees’ lack of engagement isn’t really a motivational problem. It’s a biological one. Here’s the thing: many organisations are deactivating the part of employees’ brains called the ‘seeking systems’. Our seeking systems create the natural impulse to explore our worlds, learn about our environments, and extract meaning from our circumstances. When we follow the urges of our seeking systems, they release dopamine – a neurotransmitter linked to motivation and pleasure – that makes us want to explore more.

With small but consequential nudges and interventions from leaders, it’s possible to activate employees’ seeking systems by encouraging them to play to their strengths, experiment, and feel a sense of purpose.

The power of purpose

One of the triggers that activates the seeking system is purpose. Purpose is energising. It lights up our systems and gives us that jolt of dopamine. But because purpose is personal and emotional, it is difficult for leaders to instill it in others. It’s one thing to read about something in a business book and another to put it into practice. So how do we create the feeling of purpose and make sure it lasts? To have a shot at success, you need to help employees witness their impact on others, as the case of Rick Garrelfs shows.

Rick, who was a leader at Rabobank for 18 years, told me about an experience he developed to help high-potential employees understand the meaning of their work. Working with a consulting organisation, Garrelfs and his team told the 60 employees: ‘At 5am, be at Eindhoven [a city in the northern part of the Netherlands] Central station.’ They did not divulge any further information to the participants, which naturally caused some curiosity and concerns. Some of the people called and protested: ‘But the trains are not running at 5am’ or ‘I live far away, so I will need a hotel.’ The team responded to these concerns by saying: ‘Yes, that is correct’ to retain the mystery.

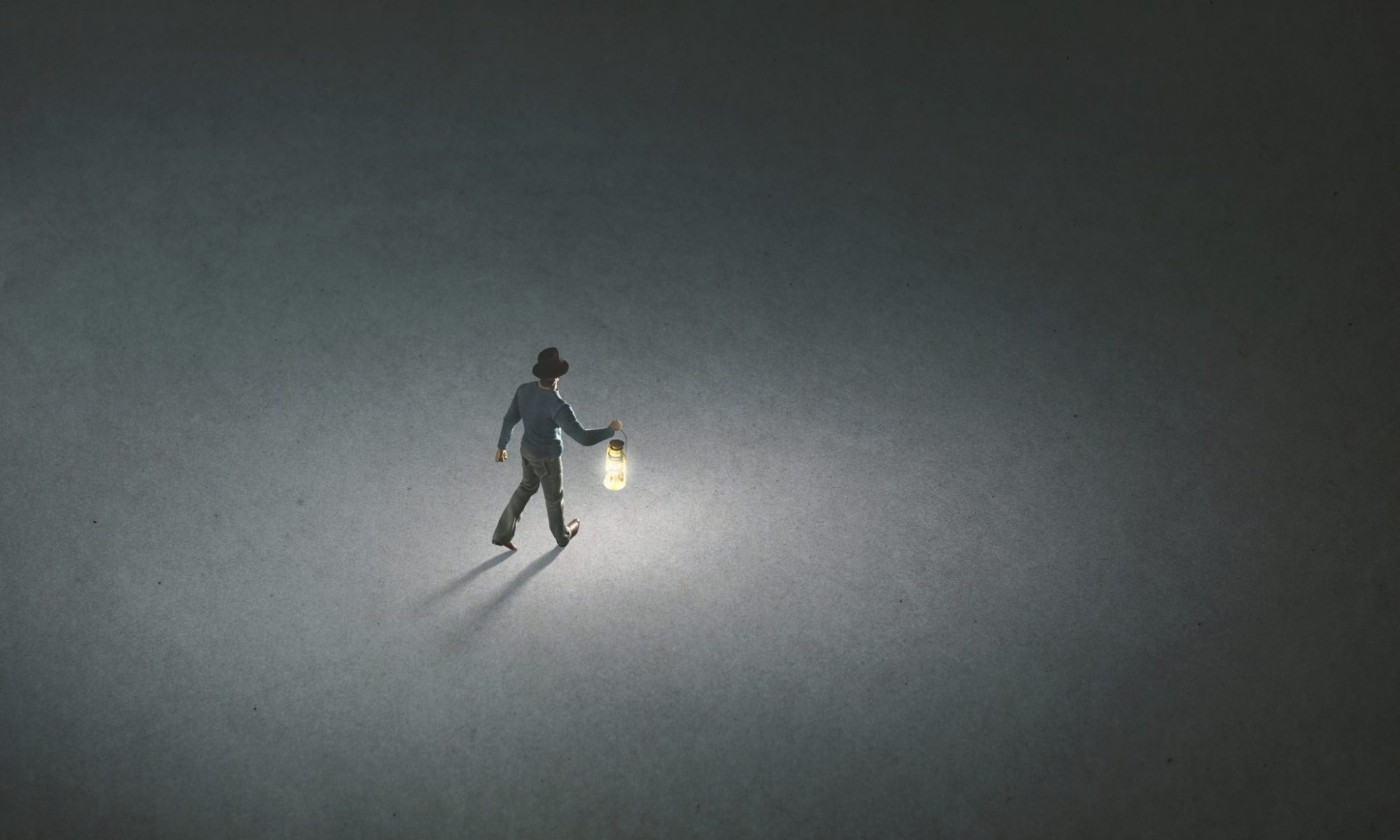

People started arriving at the station from 4:30am, and the team made sure the café was open and coffee and rolls were available. Around 5:15am, Garrelfs started walking from the station (the group followed naturally at that point) into a waiting coach, which took them on a 30-minute drive into the dark, away from town. The bus stopped, the group exited and started walking into the fields, with Garrelfs in front with a light, and someone from the consulting firm with a light at the rear.

After 30 minutes, they arrived at a line of trees, where they saw a man standing with a candle. As the group gathered around him, still in the dark of early morning, the man started to speak about the situation of farmers in the late 19th century in the southern Netherlands. He spoke about the farmers’ daily problems, their poverty, and the harshness of their existence. He described how the Dutch priest, Pater Gerlacus van den Elsen, used his local influence to bring farmers together, so that those that had some money could lend it to those that didn’t for investment.

As the man spoke, the sun slowly started to light the scene – the landscape and the group of people – and the group recognised the speaker. He was Bert Mertens, Senior Executive of Cooperative Affairs and Governance of Rabobank, and a direct report to the executive board. Bert was seen as the ‘conscience’ of cooperative thinking in the bank. His core message: Rabobank emerged from the misery of farmers, and we should never forget that.

Bert then walked the group across the farm fields, to a house where they were served breakfast by the farmers, who were long-time members of Rabobank. The farmers talked about the life of farming now, the difficulty of keeping a medium-sized farm alive, and what they did to make ends meet.

Although this had only been the start of the first day of a programme, years later the participants picked out this particular moment as perhaps the most important experience for them in terms of understanding the meaning of Rabobank.

Changing the way employees think and feel about their work

It is one thing for a leader to talk in a meeting about the mission of connecting banking to agriculture. This can be logical and strategic, and a leader can even put pictures of farms on the PowerPoint deck. It is another thing to have a personal experience: to walk in the fields, to connect with nature in the early morning, to eat and talk with the farmers who you serve as a bank.

Imagine how this firsthand experience could change employees’ stories about why they do what they do, and how it might help newcomers fashion their own purpose story. This sense of purpose could help employees make decisions that align with Rabobank’s purpose, but also help them see their work as something worth doing.

This is the power of purpose: it activates the seeking system and makes life feel better. When we understand the powerful humanistic results of purpose – not to mention the economic benefits of building purpose into businesses – then our quest as leaders changes. Our mission moves from ‘how can I make this job more efficient, predictable, and controlled?’ to ‘how can I give my team firsthand experiences that allow them to personalise the meaning of their work?’ This is a powerful new way to think about employment – as a chance to light up employees’ seeking systems instead of shutting them down.

This is an edited excerpt from Alive at Work: The Neuroscience of Helping Your People Love What They Do by Dan Cable (Harvard Business Review Press, 2018).